Katherine McKittrick, Canada Research Chair in Black Studies, Queen’s University

This conversation took place on March 28th at the 2025 AAG annual meeting in Detroit. Many thanks from everyone here at Antipode to Katherine for thinking of our website as a home for the transcript. After (or before, or while) reading it, check out the Dilla Time listening guide complied by Dan Charnas: with 300+ tracks there’s something for everyone.

Katherine (KM): Hi, everybody. Thank you for coming on the last day of the AAG to this very exciting panel on the geographies and sounds of J Dilla and the beautiful book, Dilla Time by Dan Charnas. So what Dan and I will do, just to orient you, is I have a really brief introduction and then we’re going to talk about Jay Dee’s geographies, questions of time and place, and as well the practice of writing, because it’s not just words, it’s really brilliantly put together. And we’ll have time for Q&A after, and there are books outside and Dan is here to sign them.

It’s truly my honor to introduce Dan Charnas, author of Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm. Dan is Professor at the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music at NYU and also authored Work Clean: The Life-Changing Power of Mise-En-Place to Organize Your Life, Work, and Mind and The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop. The latter inspired the co-produced VH1 movie and TV series The Breaks. His journalist work has been featured in The New York Times, NPR, Rolling Stone, The LA Times, The Source, and more. One of the early journalists of hip-hop, his writing has featured pieces on Tribe, Public Enemy, NWA, and more. I don’t want to recite his work bio or his Wikipedia bio much beyond that, but I will add that his website is very cool and it is a scroll-down like Frank Ocean’s used to be, and you can find loads of articles and interviews there. I’d also recommend his conversation with his former collaborator Rick Rubin on Broken Record, which is amazing, as well as his other discussions about Dilla. My favorite is on Sound Opinions (although it’s a little too short for me) and his conversation on Daily Detroit is terrific, too.

Dilla Time is, for me, a truly brilliant work. It’s a meticulously researched biography of Jay Dee, and it’s a clinic on different ways the production of music is underwritten by place, space, community, friendship, mentorship, family, sound, groove, and, of course, different iterations of time and out-of-timeliness. Charnas provides a deep history of hip-hop and the work of reimagining Black music; he presses us to think through how and why Jay Dee troubled normative sonic landscapes—on his own or through his work with folks like D’Angelo, Q-Tip, Slum Village, and others. He also breaks down how Jay Dee reconfigured the purpose of drum machines, snares, and vinyl records. The book also meditates on health, wellness, and creativity, drawing attention to how Jay Dee, in the last years of his life, moved through the world uneasily. His dedication to music and music-making at this time were animated by pain, hospitalizations, and care work. Also important, for me, are the pedagogical workings of this text. Drawing inspiration from Dilla, Charnas teaches us to listen to and make beats. He provides a set of instructions that map out how Dilla reordered time. He gives us the courage to move to music while we read, and also stop reading and listen to music—it is sometimes important to stop, listen, chill, as Kara Keeling encourages. He teaches us to understand funk and swing as measurements of time and gives us the visual and sonic tools to notice how Dilla Time, Jay Dee’s work of experimenting with error, radically subverts how we know and feel music.

Our first prompt is about geography. There are many geographies underpinning Dilla Time: basements, homes, studios, hospitals, churches, daycares, or airports, Canada, Europe, USA, gentrification, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and of course Detroit. There are also street names and even musician names—like Slum Village. The book begins with maps of Detroit, land ordinances, grids, spokes, 8 Mile, and more. Later in the book you write of the mourning of Dilla’s friend and colleague, Shoes, how his grief was tied to the city; Shoes describes his work as an ambassador of the city of Detroit, and his commitment to Dilla is animated by his creative labor, which, as I read it, is a labor for the city. It is creative labor in service Detroit. And perhaps Shoes is asking us to acknowledge the labor of Dilla’s Detroit. Can you talk about how Detroit shapes Dilla’s narrative? You make deliberate connections between city plans, what you describe as “a design of rigid mathematics in multiples of three, imposing its order on the American landscape and upon everybody within it”. And you think about that alongside the European rules of music, and you make meaningful connections between the production of space, the production of music, and Detroit. Is Dilla Time Detroit time?

Dan (DC): Yes. Well, first of all, I didn’t have a chance to say thank you for that lovely introduction, and thank you all for coming out. Hello, geographers. I’m not a geographer. I am a journalist by trade who was an urban studies and African American studies major in college, but when I was 10, I wanted nothing more than to be a cartographer. So in a real way, this is a dream come true for me.

KM: Incredible!

DC: Yeah, awesome. So maybe we should just start with Detroit and then move out from there. Detroit, my first trip to Detroit was to work with J Dilla, who was then known as Jay Dee. I was in the music business—I should have been a cartographer, actually. And nine years later, I had met my current partner, Wendy S. Walters, right there, who is from Detroit, and so that was my second trip to meet her family, and Wendy gave me my first sort of real survey of the city, and that became a backdrop for me as I began to teach at NYU. I teach music history, popular music history. And I found that a lot of my students—who weren’t even alive really when J Dilla, when Jay Dee was making music—just love Dilla, so I ended up teaching a class on Dilla, taking 20 students from New York to Detroit for that class.

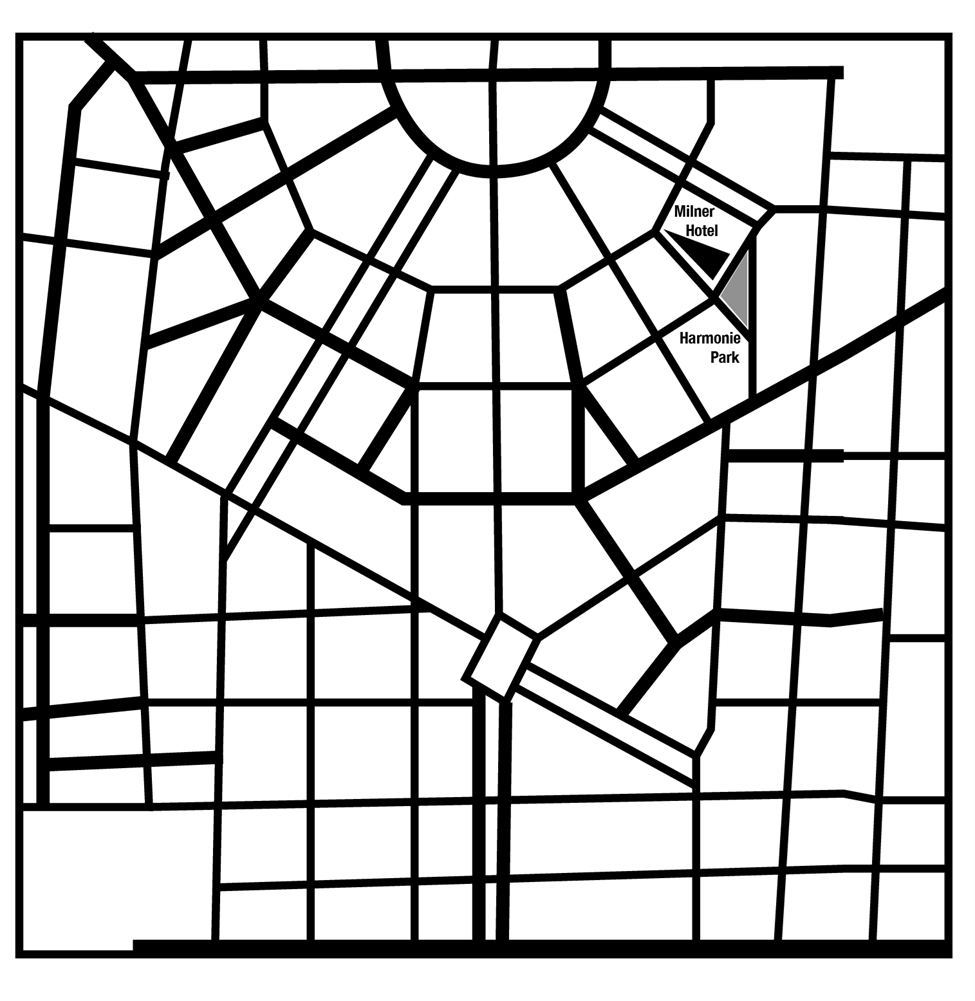

And then, of course, Detroit became a part of that, and Detroit has one of the more interesting maps of any city. I became obsessed with it as I made Detroit kind of a second home. The commissioner’s plan of Manhattan, where I was born and where I live, it’s designed for and facilitates capitalism, right? A grid is all right angles. It’s twos and fours. But the original plan and idea for Detroit, as you can see here, was radial. It’s all threes and sixes. And radial plans, hexagonal plans are harder to navigate, they create angles that are more or less than 90 degrees. But it’s also beautiful, right? So in a certain mode of thinking, the grid can represent the logical. The linear and the radial or hexagonal can represent the artistic and the creative.

Now, twos and threes can mesh, right? Fours and sixes can mesh, but they have to be aligned perfectly, and if they’re not aligned perfectly, then they are colliding, they’re in conflict. And so, Augustus Woodward, this was his plan for Detroit. He was very much a fan of all things European. So it was a colonial plan in many ways to enforce this grand European design on this landscape. And this was the original plan for downtown, beautiful, all threes and sixes. But there was a problem with this is, is that the people who lived here, especially the merchants, didn’t like that plan. So when it came time to actually build this thing, you see there’s a fort right there on the left-hand side, and the fort was the last to go, so the merchants decided that they were going to sabotage Woodward’s plan and put a grid of twos and fours next to his triangle of threes and sixes, except it’s not really aligned, is it? It’s in conflict.

And that stayed. So, you have Woodward’s original design for this monumental city of threes and sixes, the merchants wanted a navigable city of twos and fours, and the sabotage continued. Lewis Cass, when he became governor of Michigan, he capped all those triangles that Woodward wanted to make right at, I forget what that street is, but Grand Circus Park was supposed to be a circus, was supposed to be a circle, and it’s just a half-circus really. And you can see even the grids are all different. They’re not aligned. The farmers on either side of this downtown sold off their lots piecemeal and kept those sort of really wildly-angled north-south roads. And then Jefferson, when he became president, he enforced this kind of geocolonial, these east-west aligned mile roads.

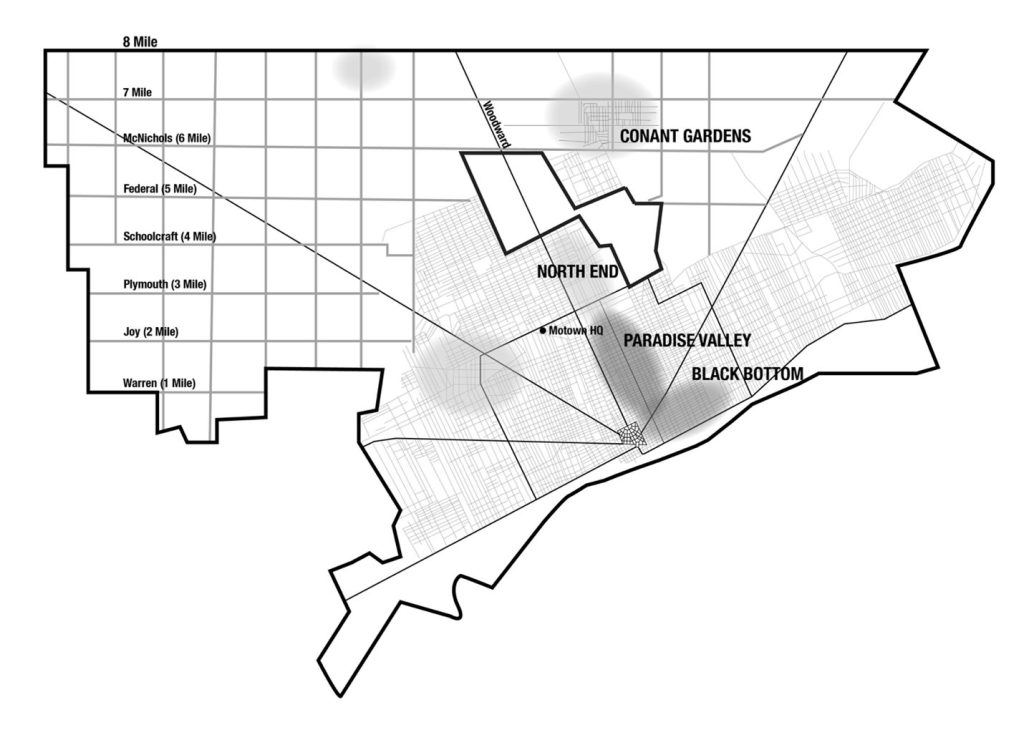

So the Detroit that eventually became Detroit, you can see it has at least three different grid plans. There’s that original kind of shattered shard of Woodward’s plan of threes and sixes. Then there’s the merchant grid of twos and fours, but it’s really aligned with the river. And then you have this other alignment with geographic, cardinal directions. And so Detroit in that way is a map of all of those disparate intentions over the years. And you can see also on top of this map is where Black Detroiters were permitted to settle, first in Black Bottom, then in Paradise Valley, which used to be a Jewish neighborhood. And Hastings Street was the main thoroughfare of Paradise Valley where all of the institutions of culture were.

And of course, that underwent another kind of sabotage in the 1950s and 1960s, when the highways were built. There’s this very famous speech that Malcolm X made at the King Solomon church called “Message to the Grassroots”, and it was just after the March on Washington, and he was trying to make a point that the march wasn’t a top-down thing, it was a bottom-up thing, it was organized by people on the ground. And he said, “You were talking that march talk on 125th Street and on Central Avenue”, referring to the main Black thoroughfares of all these cities. And then he says, “You were talking this march talk on Hastings Street”, and then he says, “Is Hastings Street still here?”

KM: Yeah.

DC: And it wasn’t.

KM: Right.

DC: Right? That’s the Chrysler Freeway, the future Chrysler Freeway. They just erased it and Black Bottom from the map. So what does all this have to do with J Dilla? Well, I will say this, that when I teach music and music history, I teach it in terms of its context. Every musician, they have a musical context, but they also have a geographical context, they have a familial context, they have a racial-ethnic context, they have an economic and political context. And so that’s just how my mind works, and at a certain point, when I was turning this class into a book, I had a bunch of contextual chapters that you needed to read in order to understand J Dilla. I got to have a chapter on Detroit and the map of Detroit and how Detroit got settled. Then I have to have a chapter on his family and how they got here. And then I have to teach music theory. And I’m like, “Nobody’s going to read all this shit”.

And then just looking at the map, it’s all there. All of those lessons are in one. I can teach polyrhythm with this, but this actually looks to me like Dilla’s rhythms feel, right? It’s an internally conflicted polyrhythm of threes and sixes and twos and fours, but they’re not all aligned, and that’s actually what a Dilla beat is, and he was born right there. That’s where he lived. That’s where he first started making music as a two-year-old in Harmonie Park, spinning records on his little Fisher-Price record player. And the story of the Great Migration is there, and the story of the Ford Motor Company is there, and everything is there, so the map became a way to tell this story and a way to teach what he did. And I know that’s only probably a partial answer to your question.

KM: No, it’s great, because one of the things I think a lot about in terms of geography and Black geographies is how identity and place are mutually constructed. And so you do need this kind of deep context of the city, of Detroit, and of the production of space to better understand Dilla. And I’m also thinking about Dilla and his family and his community walking around these streets and the grids and how these layers of history push through. And I don’t want to fetishize the metaphor too much and imply that this map made the music, right? But at the same time, as you’ve noted, these ideas around Black history and displacement—these shifts in place impact your worldview, that’s how you navigate the city and that’s how you make music as well. So it’s just beautiful. Thank you for that.

I wonder if you can give us a lesson in Dilla Time? One of the reasons I love this book and your research and writing is because you pay such close attention to time and Dilla’s reworking of rhythm, tempo, straight time, swing time. In this book, you also touch on our physiological responses to the groove. So for those who know me, this is a Sylvia Wynter project in disguise. There is a meaningful relationship between the physiological, the geographic, and the production of music. These relations are so deeply enmeshed in this book. And the way you have written the book really centres not just music ideas but how we feel and move to music. You give us music lessons and activities in the book and that it’s just incredible. There’s something about the embodied lessons that you share that make this book and your research really special. This is a study that asks that the reader engage deeply in the practice of listening to music. That’s important! Your book gives us the gift of doing music. There are instructions on how to measure blues time and funk time. There are charts and lessons where we’re asked to stomp, clap, and count. Can you talk about normative beats and elastic beats and how Dilla reimagined time, and talk about a bit how his sense of time is so unique? So I really want just a little lesson here on this practice of making music, the stomps and claps. The creative labor of altering time helps us understand his story, but also, as I’m here with you, I’m also thinking, “Why did you put these lessons in here?” I think it’s just so genius to have instructions in there, that say, “Do this, make this sound…”

DC: Yeah. Well, thank you. I also want to say you gave me an essay that I think was a chapter in your book, Dear Science, if I’m not mistaken, and one of the things you talk about are the rigid boundaries between disciplines, and I was fortunate enough… I mean, I have disciplines, but I am not, I suppose, at an institute that guards and fetishizes those boundaries.

KM: Yeah.

DC: And those boundaries are everywhere, not just in academia. I mean, if you talk to Robert Glasper, a jazz pianist, he will always talk to you about “the jazz police”.

KM: Right.

DC: “You can’t blend this with that”, right? Or, “It’s not pure”. And there is something, as you wrote, so colonial about that. And so for me, I was in a place and in a state of mind where pretty much everything I do is kind of in between the seams, and that’s a blessing and a privilege to be able to do that. But yeah, so I’m like, “How else are you supposed to do it?”, for me.

KM: Yeah, yeah.

DC: And that’s what enables that, using that as pedagogy. So, beats, rhythm, a biography of rhythm. So do you want to help me do some exercises? Can you use your hands and your feet? Okay. So we’re going to talk about monorhythm and polyrhythm. So what I’m going to do is I’m going to clap my hands, and I just want you to follow along with me. Just clap with me. And then when I do this [puts palm forward toward audience] it means…

KM: Stop?

DC: Stop, exactly.

KM: Okay.

DC: Okay. And we’re going to need this because we have to try a couple different things. Okay, so just simple exercise. This is a monorhythm. Clap. [audience claps a steady rhythm]

Very good. Okay. That’s a monorhythm. That’s one pulse, right? Now we’re going to try two different monorhythms, and I have west side and east side [points down the middle of the audience], and you, my friend, are right on the dividing line here, so you get to choose whether you’re west side or east side. So this is Woodward Avenue right here, right down the middle, okay? All right, so west side, east side. Now, east side, don’t do anything yet, right? I’m just talking to the west side folks. So what I’m going to do, I just want you to listen to my pulse a little bit, okay? [claps an even pulse of twos]

Can you do that with your hands? Okay? Try that.

Stop. Okay. Now I’m going to give you all the same beat, right? Same timing, this pace, this tempo. But at this tempo, we’re going to divide that. Instead of dividing it into two, we’re going to divide it into three. So it’s going to sound like this. [claps an even pulse of threes]

So, go.

Now keep going. Don’t stop.

Now you guys are going to follow me, what I do right now. [one half of the audience claps in twos, the other in threes, simultaneously]

KM: It’s hard!

DC: Good, I thought that was pretty good. You’ve just done collectively a polyrhythm, right? There’s two rhythms, one and twos, one and threes, and you can hear there’s a little tension between the two, right? So, if I were to do it myself, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3. [demonstrates a polyrhythm by banging hands on chest]

KM: Yeah.

DC: Right? Okay. Monorhythm is essentially what the European common practice was. The West African common practice was polyrhythm. And when Europeans encountered Africans in their colonial project, this seemed alien and a bit scary to the Europeans. And so when Africans were brought to the Americas, that polyrhythm survived in South America, and that’s the polyrhythms that power Caribbean and Brazilian music especially. But they did not survive in North America because captors were harder and more stringent on enslaved Africans in North America. So, polyrhythm did not survive in North America. Instead, it got squeezed into the monorhythm. It became what we’ve come to know as swing. That’s the West African retention squeezed into the monorhythm of North America. So if this is a polyrhythm, two’s on the top, three’s on the bottom, swing is what happens when you eliminate that, when you merge the first two. And so swing is that track on the bottom. And so what we have here are two different conceptions of rhythm and time. Straight time, which is the European inheritance, and then a uniquely African-American invention called swing, which is uneven beats. And that’s what ends up powering blues, that’s what ends up powering gospel, that’s what ends up powering jazz, and rhythm and blues, and rock, and on and on and on. Does that make sense?

KM: Mm-hmm.

DC: Okay. So I want to do another little exercise. Are you okay with these exercises? Am I wearing you out?

KM: No, it’s good.

DC: So we’re going to do a little exercise to just demonstrate the difference between straight and swung. And once you’re able to understand that, then we can understand what Dilla Time is.

KM: Okay.

DC: Okay. So how many of you know, are familiar with this song? [plays “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen]

MUSIC: “Is this the real life?…”

DC: Does anybody know what this song is?

KM: Yes.

DC: What is it?

AUDIENCE: Queen. “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

MUSIC: “Escape from reality…”

DC: Now, most of this song begins as an opera, and an opera is in what cultural tradition?

AUDIENCE: European.

DC: European, right?

MUSIC: “Any way the wind blows doesn’t really…”

DC: But there’s a moment in this song at around four minutes into it where it’s in this really, really powerful opera session. And then within 10 seconds, it’s going to morph into rock and roll. And essentially what that means is it is going from straight time to swing time. So what we’re going to do is we’re going to double-time clap along with that opera rhythm that’s straight, and you’re going to actually feel the transition to swing. Okay.

KM: Okay.

DC: So we’re going to clap at like this kind of speed. You don’t have to do it now. It’s going to be like that, right? Okay. So here we go.

MUSIC: “Let him go / Bismillah, we will not let you go / Let me go / Will not let you go / Let me go…”

DC: Very straight.

MUSIC: “Will not let you go / Let me go / Ah / No, no, no, no, no, no, no / Oh, mamma mia, mamma mia / Mamma mia, let me go…”

DC: Here we go.

MUSIC: “Beelzebub has a devil put aside for me, for me, for me.”

KM: Yeah.

DC: Right.

KM: I love that.

DC: Do you feel the difference, right?

KM: Yes.

DC: One is even, very straight. One is uneven. And these two time feels have been a part of our popular music expression for over a hundred years now, 150 years. Ever since sort of ragtime and blues came into our culture. And there are gradations between them. That’s why swung rhythms are so hard to notate using the European notation system of notes and staves and things like that, because swing is actually a corporeal expression, it’s an expression of the body, and everybody’s body moves a little different.

Okay. So these were our choices… until 1998, when a beat producer in Detroit, in Conant Gardens on Nevada and McDougall, in a basement found a new way to make rhythms. So here’s another geography for you. It’s the geography of the drum machine, the sampling drum machine. And this is in many ways the province of the grid. It’s machine clocks, and machines are all, especially digital machines are all ones and zeros. You’re either on or off. And that’s hard when you’re a human being trying to make music on a machine, because human beings don’t place notes perfectly. You can see up top, right? Those are very imperfect placements, because a biological organism is a lot more complex than a computer organism. And so some drum machines, like the one I just showed you, created ways to correct that imperfection. But then when you correct the imperfection, it loses the charm, right? And so here was J Dilla’s quest to try to find something. And if you want to know why he went on that quest, I can play you a little video clip later as to what I think his “rosebud” moment was.

But the point is that this machine actually allowed him to experiment in ways that even real drummers couldn’t with how to play with notes. Instead of swinging everything, you could swing some things and not swing others, to put those beats in conflict with each other. You could slide notes around their placements. And what happened with that essentially is he started doing that, and it gave us this… It didn’t have a name when he first started doing it. It was just, “Oh, that Dilla feel”, right?

KM: Yeah.

DC: And these are the adjectives that people used to describe it. [points to slide with adjectives: “limping, drunken, lazy, sloppy”, etc.] And I want to play you an example of this. And here’s the thing, a Dilla beat is very much like… These manipulations of time are so small. They’re in milliseconds. Some people really feel them and some people don’t. And it all depends on what your nervous system is. It’s almost like the Princess and the Pea. No matter how many mattresses you stack, I’m still going to feel that pea on the bottom mattress. So I’m just going to give you an example of what one of his… I’ll just play you a few of his beats. This is one example that’s really exaggerated.

There’s an element that’s very, very straight, but then the relationship between the kick and the snare is uneven. Do you feel that thing coming in? Here’s another example.

That hi-hat is swinging, it’s uneven. But then other elements are going to be perfectly straight and it’s going to limp. And he started putting out music beats around 1998, 1999 with this and almost immediately his circle of admirers, which also included traditional musicians like D’Angelo and Questlove, started to imitate that sound on traditional instruments. So this is probably the earliest example of D’Angelo and Questlove trying to maintain this really weird tension. It’s easy for a machine to do because once you program a machine it’ll replicate all that stuff. It’s hard for musicians to do it because musicians want to be in consonance with each other. So this is an example of traditional musicians doing this.

You can hear Questlove bringing in that snare drum just a little early. And so often it’s all these different elements sort of pulling and pushing against each other. So when I started teaching this class, I wanted to give it a name. It wasn’t straight, it wasn’t swung. It was straight and swung together, the deliberate cultivation of conflict between straight and swung song elements. And so I created sort of a third installment. And you can see that in Dilla Time, there’s a certain freedom. You can have some elements that are straight, some that are swung, some that are offset, but often when I expressed this, when I first started playing around with this idea, I actually used the map of Detroit to express that final one because that’s actually what it feels like.

KM: Yeah.

DC: Do you have a sense of what Dilla Time is now?

KM: Yeah.

DC: And I just want to say, again, I know this is a long answer to your question, but—

KM: No, no. We need the length!

DC: This is an innovation of centenary importance, like the idea of codifying a new rhythmic feel puts Dilla as a humble beat producer in the same league, I argue, with a Louis Armstrong, who helped to codify swing into our musical vocabulary, or Billie Holiday, who did the same, right? Or Duke Ellington, or a John Coltrane, or a James Brown. He’s that important. And so that’s the reason it’s a long-ass book.

KM: Yeah. It’s so long, but it’s so good.

Can I add just another question around this?

DC: Yeah.

KM: There’s a moment in the book where you talk about Questlove relearning the drums—can you talk a little bit more about that, because I think that there’s also something incredibly interesting about being taught in a particular way and then unlearning it. So I’m thinking about unlearning it and then re-imagining a beat, while also retaining what you originally knew.

DC: Yeah.

KM: If you can talk about Questlove’s work as a drummer. And I don’t really want to bring up Kanye, but I will! I remember Kanye said that J Dilla is the best drummer on the planet or something. I forget what the quote is. J Dilla was also a percussionist. Can you talk about this aspect of his life?

DC: I can. And I’ll start with Kanye and I will start by disagreeing with Kanye, that a lot of times what we do is we, again, it’s a part of this sort of colonial reflex. We transpose what we know onto a reality that we don’t necessarily have a language for. One of the impetuses for writing this book is people said, “Well, Dilla just turned off the timing functions of his computer and just played free”. But he’s not a drummer. He’s a programmer. He didn’t turn off the timing functions. He actually used them.

And then here’s another thing that always bothered me. They would say, “Dilla has a great feel”. That’s why I didn’t like that word, feeling, because he has both things, he has feel and he has intention, he has feeling and he has method. There’s a logic and intelligence to what he’s doing and a feeling to what he’s doing, and if you have the feeling but you don’t have the method, you won’t have an ability to do what you’re doing. And so that’s what happens. As somebody who teaches popular music, Black artists get that a lot.

KM: Yeah, I’ve written about that, about the “natural” musicianship of Hendrix or others, and how this tag assumes they don’t practice or study!

DC: “They’ve got such a great feeling”, right?

KM: Yeah.

DC: But it’s also about the science. He was a scientist. So he had both.

KM: Yeah. And later in the book you say he’s a programmer—this is the work he’s done, it’s programming work.

DC: Yeah. And I will say this, Questlove has his own interesting story. So many of you know Questlove from what he does now, right? He’s an Oscar-winning film director, he’s drummer with The Roots on The Tonight Show. But he was a struggling musician. The Roots were not a headlining band by any stretch of the imagination in the middle of the 1990s. And when The Roots first came out, a lot of folks in hip-hop kind of, not laughed at them, but they felt The Roots sounded like a jazz band playing at hip-hop. And one of the big tensions for Questlove with his partner Black Thought in The Roots is Black Thought wanted the sound of these rigid programmed drums. And so Questlove had to train himself to get all the sound of error out of his playing. And then he hears Dilla and he says, “That’s what I want”. And he languaged it as “sloppy”, but it wasn’t sloppy. It was filled with intention. Every single note event was where Dilla wanted it to be.

So Questlove tells a very funny story of when he was in middle school or high school learning from his drum teacher, Jules Benner, and Jules Benner had him do this exercise where he was playing in twos with his feet, but then playing with threes with his hand, just like you all were doing before, hours and hours on end while Jules Benner read the paper and smoked his pipe. And young Ahmir Thompson is thinking, “I am never going to use this. I’m never going to use this”. And then along comes Dilla, then he has to use it, right? Then he has to find a way to maintain not only that tension, but an offset tension, a snare that comes in a little early, but in such small increments that you can’t really count it.

Some drummers try to count it. They call it a septuplet. There’s literally drummers who count in sevens to try to get that Dilla feel, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3, and you move everything a little earlier by one of those sevenths, by one septuplet. And even that, it’s just an approximation of what Dilla was doing on the machine. So there’s lots of different techniques that humans have done to replicate this uncanny machine music that sounds human, and it is because it is part of a long tradition, and I credit Arthur Jafa with this phrase, a long tradition of misusing the equipment in the African-American tradition.

Blues was mainly played on the guitar, but the guitar has the European scale, that chromatic scale built into the instrument. But the West African impulse, the African-American impulse is what we’ll call microtonal. So how do you get to the notes between the notes? You can bend the strings to get them or you can use a bottleneck, like a glass bottleneck, and that gives you the blues scale. The blues scale isn’t simply a flat third and a flat fifth. That’s an approximation. The real thing is the notes between the notes.

So that’s an example of misusing the equipment. When Monk puts his whole palm down on a bunch of keys to get to the notes in between the notes. Or when Kanye jacks up the auto-tune in ways that it wasn’t supposed to be used. Or when Dilla uses the MPC to make some elements swung and some straight. I asked the architect of this machine, Roger Linn, the guy who built it, “Why did you do that? Why did you make a machine that enabled people to have some elements swung and some not?” And he said, “I don’t know”. So even the architect didn’t envision that the machine would be used that way.

KM: I’m going to go to our third prompt, which is about writing. This book is monumental. It is thick and heavy. It’s a bit of a kettlebell. Dan and I have talked about, just very briefly, how I’m a huge fan of artist biographies and autobiographies, and when I finished this beautiful book, it moved to the top of my favorite list alongside Richard Pryor’s brilliant and heartbreaking Pryor Convictions and Charles Mingus’ Beneath the Underdog. As a genre, the biography and autobiography and life writing, these are unique ways of telling stories. They historicize, they map, they contextualize, they stretch the truth (à la Mingus). They paper over hardships just as they expose them. If a musician or artist is the subject or author of the study, the narrative gets bound up often in stardom, and as readers, we’re given a window into creative genius, and traumatic childhoods, and different iterations of desire, loss, and hope, and this is where we read of Britney Spears’ carceral life, Gram Parsons’ love of sequins, and what Nina Simone describes as the casual horror of a performer’s life.

So in your preface, you discussed the work of humanizing Dilla and his family and his comrades, and throughout the book, there are footnotes and commentaries that open up conflicting stories and different perspectives, which was so great. And at the end of the book, after Dilla’s death, there’s this scramble to own him and commodify him, and that is real, and the way you describe it is real, and it’s heartbreaking. Can you tell us about your research and writing process and the difficulties and barriers and possibilities you encountered while threading together this project?

DC: Yes. This was a difficult project to envision doing because it was thorny from the very beginning because Dilla’s posthumous legacy had been one of contention between members of his family, between family and friends. And for me, I think it just started with the idea that, “Okay, I’m teaching this class about Dilla, but nobody is getting the musical part of it right, so let me just write this tiny, thin book about his musical genius”. And what happened to me in the process of pitching and writing that book is that the reporter’s muscle took over, that once there’s a question, that leads to two other questions. Once you talk to one person, you realize that there are two or three other people that you need to talk to, so it ended up being something like 200 people over the course of 400 years… Sorry, no, Freudian slip. Four years.

KM: It probably felt like 400 years.

DC: Four years. It felt like 400 years, especially to Wendy. Oh, God. Yeah, and it was really all about order, who do you speak to first, because also, folks are very protective of James. So who do you speak to first? Who can you honor, right? So there were a couple of methods that I used. The first was the readback, which I think is really important. I write in the third person omniscient, which means I’m writing from behind the eyes of my characters, not just quoting them like you would in a newspaper or a magazine article. So that requires complete accuracy. Usually a reporter does not want to give control of their material to their sources. So if I interviewed you for a newspaper article, I might read back to you the quote for accuracy. But I read back entire sections to folks because I wanted them to see the context in which they were portrayed, because I wasn’t quoting them, except if they were speaking to somebody else in real time.

And there’s a risk in that because somebody could listen to you and say something like, “Well, don’t write it like that”. I rarely got that. What I mostly got was, “Oh, wow, you got that right”, or they would laugh. Sometimes they’d say, “No, no, that’s wrong”, which was super important, and I would read, and read, and read, and read, and read until I was sure that it was right. And then if two people were in a scene and they were both alive, I would read it to both of them. And that was the methodology, and the byproduct of that methodology is trust.

So there were people who said no to me. One in particular was the mother of Dilla’s second child and his longtime partner, one-time fiancée, Joylette Hunter, who had felt, along with her daughter, erased from history. And so she said no, and I said, “That’s fine. Look, I just want you to know I am going to be writing about you in this book. So when I’m done, I’m going to call you, I’m going to read you what I’ve written. You don’t have to say anything”. And she says, “Okay, that’s fine”. And so I left it alone. But I had interviewed enough people around her and read back to them what I had written that she eventually called me, and then she was ready to talk, and we talked for six hours, and by the end of the call, she was crying, I was crying, it completely transformed the book. Moments like that. Q-Tip said yes and then he said no. And then he said no and then he said no. And then it took House Shoes… it’s House Shoes’ birthday today by the way, 50 years old…

KM: Yeah, nice.

DC: The guy who really, more than anyone, championed Dilla’s music in Detroit and elsewhere. It took Shoes to basically tell Q-Tip to talk to me, which was great.

And then the last, I was in Detroit completing the manuscript, it was like two days before it was due, and I’m sitting at the dinner table with my wife, my son, and my mother-in-law, and the phone rings. I look at my phone and it’s D’Angelo calling. And I leap up from the table and I go to have that call with D’Angelo, which lasted for two hours, and it was great, but my mother-in-law is still angry with me for getting up in the middle of dinner. She still talks about it.

So yeah, it’s a lot of the fear of getting it wrong, I think, which is a common fear for journalists. But I believe that the best academics and the best journalists have the same ethics, right? We want to get it right, and we’ll do anything we can to make sure that we get it right, whether it’s in the data or whether it’s in the reporting, whatever it is. So I was just trying to get it right.

KM: Yeah. Joy’s story is so interesting, the way it’s threaded through the book but also how it kind of comes a little bit late, almost like a lagging. It comes and goes at different frequencies. That’s so beautiful.

DC: Can I show one thing before we end?

KM: Yeah, of course. Please do.

DC: Just to end the whole geography thing, J Dilla is now a more official part of Detroit geography. This happened just last month. Nevada, near the corner of Charest, between Charest and McDougall, where his house was, was officially named J Dilla Street. And those are his two daughters, Ty-Monae on the left and Ja’Mya on the right, holding the first official proclamation from the City of Detroit declaring February 7th, his birthday, official J Dilla Day. So I feel really good about that.

Photograph and maps courtesy of Dan Charnas, with thanks.