Maxim Tvorun-Dunn (University of Tokyo)

It is no secret that academic writing is built on unequal and exploitative relations with the publishing industry, wherein the largely unpaid act of producing and reviewing research disproportionately benefits a select few publishing magnates. Today, however, academic writers face new disparities in their relations to publishers, through the non-consensual licensing of academic writing as data to train machine learning systems.

Geography literature has, above most fields, critically engaged with the role of human labor in the extraction of value from data. Thatcher et al. (2016), Mezzadra and Neilson (2017), and Doorn and Badger (2020) have examined the extraction of data from platform-mediated activities as a form of Harvey’s (2003) “accumulation by dispossession”, or Marx’s “primitive accumulation” wherein new forms of capital are created through processes which divorce “the worker from the ownership of the conditions of his [sic] own labour” (Marx 1976:874). These authors discuss that the extraction of value from one’s actions and behaviors, in the form of data, alienates workers from the meaningful control and ownership of their own actions. Data, when gathered in sufficient quantities, becomes an asset for capitalists. This data can be exchanged into capital through the extraction of rent in platforming access to this data, or through the production or optimization of services derived from this, and can be used to attract venture capital (Birch and Ward 2024; Doorn and Badger 2020:1477). In each of these ways, the outputs of labor are indirectly deposed and turned into capital through the accumulation of data. Today, however, there is a much more direct form of dispossession of our labor ongoing: the accumulation of text into the training sets of Large Language Models (LLMs), a machine learning format which has been encompassed under the umbrella marketing term “AI”.

In this short essay, I will argue that using academic writing to train the products of billion-dollar tech firms constitutes an act of accumulation by dispossession. I will demonstrate that the meaningful ownership of our texts is being expropriated through the extra-legal accumulation of publications into AI datasets, as well as through their subsequent plagiarism by these language models. Lastly, I will examine how academic publishers are profiting from this expropriation of our labor, without any return in compensation to authors or mechanisms by which to opt out. I am not here concerned over the use of ChatGPT as a form of cheating in education/academia, or that AI will replace writing, as some have feared. Rather, I argue, firstly, that these algorithms inherently operate on the basis of plagiarism, and secondly, that the appropriation of our work into these datasets is producing a form of assetized value which has been produced by our labor but for which we are neither compensated for, nor have any practical ability to withdraw from or seek legal recourse against.

Certainly, academic writing has already succumbed to several previous regimes of accumulation by dispossession. The 1980 Bayh-Dole Act (and its international equivalents such as the 1999 Japanese Industrial Revitalization Law), and later the 1995 TRIPS agreement, privatized information which had earlier been part of the public commons, transforming knowledge into an asset of “intellectual capital” (Yan 2024). Academic writing has been accumulated and consolidated to support the valuation of powerful conglomerates. As Yan (2024:6) notes, in these prior forms of enclosure, “the separation is not between the worker and knowledge itself”, as authors do retain certain rights to their own work, “but between the worker and the ownership of the conditions for labor (knowledge)”. Today however, this caveat, that workers had not been separated from their work, is in the process of being overturned.

Large Language Models, such as ChatGPT, rely on “training” datasets from which they will algorithmically predict what information to retrieve and display from a user’s inputted prompt. LLMs function by accessing a vast repository of millions of texts, which they use to predict how a human author would respond to the prompt, at times reproducing training data verbatim (Carlini et al. 2022). By their very operating principle, LLMs depend on the accumulation of millions of texts in their data sets, a process which requires the “scraping” of text sources, through which text is copied and added to the data set to contribute to possible outputs (Fontana 2025). Because LLMs are able to reproduce this training text verbatim, their output is structurally dependent on the ability to reproduce previously authored texts.

Due to the scale of the data required for these algorithms to work, AI firms have been known to play fast and loose with intellectual property laws. OpenAI and Meta have been accused of using tens of thousands of texts in their AI datasets which had been acquired through pirated sources such as Sci-Hub, LibGen and Anna’s Archive as well as through torrenting (Morales 2025; Reisner 2023). While acts of piracy are certainly a useful source for marginalized authors/readers, providing access to resources whose restriction stems from past eras of accumulation by dispossession, there is clearly a difference when billion-dollar tech firms utilize these resources to extract value from uncompensated sources. The extraction of value from this data is not only siphoned from our labor as authors, but these texts must be manually annotated and curated to become usable in a language model, labor which is done predominantly by workers in the Global South and/or by prison laborers (Kaun and Stiernstedt 2020; Posada 2022).

Because these are merely complex algorithms, LLMs have no creativity, and instead rely on the ability to copy prior sources. Thus, these billion-dollar companies are extracting value through the reappropriation of texts from other authors’ labor. In other words, because these companies can copy our results and text in the production of AI outputs, including as full publications, we essentially have no meaningful right to the ownership of our labor. If AI firms are able to profit from the reappropriation of our labor so long as it has been submitted to a training set first, then there is little stopping the algorithmic plagiarism of any text, as has been visible within the news industry for the past two years wherein articles in major outlets are being algorithmically rewritten as separate competing products (Seife 2023). Similar concerns have been raised within the arts and entertainment industries, where voices and artworks are algorithmically repurposed into competing texts (Milmo 2024). In addition to the direct plagiarism of training data used to produce verbatim or rephrased output text, LLMs regularly intermix outputs with “bullshit”—Hicks et al.’s (2024) term meant to counter the industry-friendly “hallucinations” used to describe incorrect information produced by LLMs. Because LLMs attempt to algorithmically predict the most statistically likely combination of words to reply to a prompt, they do not have any means to comprehend or verify information, and will regularly provide incorrect content which appears linguistically probable. Therefore, LLMs are particularly likely to misrepresent, mis-cite, or entirely fabricate published information, contributing to an alienation from the labor of writers when their work is plagiarized or misrepresented by an algorithm trained on this data. As an example of the stakes of such misrepresentation, on March 5th, a pro-Palestinian researcher at Yale, Helyeh Doutaghi, was suspended when a news site published an AI-generated article claiming that she was a member of a designated terrorist group (Saul 2025).

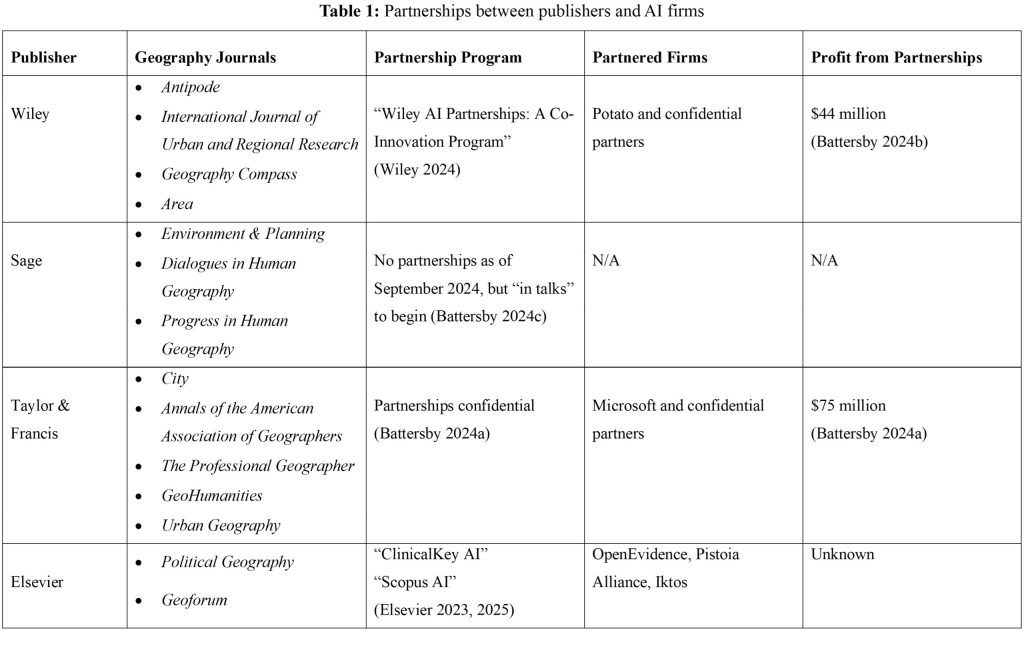

Despite, and in part because of, this ongoing theft of data, every major academic publisher, including Wiley (who publish Antipode), Taylor & Francis, Elsevier, and Sage, have announced partnerships, or plan to form partnerships, with AI firms to provide papers for machine learning datasets (see Table 1). None provide any systems of consent for journals or authors to oppose their inclusion.

Wiley has announced that they have “decided to lean in on AI”, claiming that “our view is that society benefits when AI models are trained on high-quality, authoritative content”, and that they have ramped up efforts towards “AI publishing” (Carpenter and Jarrett 2024). They advertise that they can provide partners with “an extensive library of peer-reviewed content” to ensure “reliable and accurate AI applications” (Wiley 2024). As reported by publishing news outlet The Bookseller (Battersby 2024b), in 2024 Wiley earned $44 million in confidential partnerships to license the works they own to AI firms. In other words, Wiley has provided the “extensive library of peer-reviewed” articles which they hold rights on to be recycled and reused to train the algorithmic and plagiaristic production of publications designed to compete with scholarly writing. Though these licensing agreements may affect authors’ choice of where to publish in the future, there is no way to revoke consent from works which have already been published.

Taylor & Francis has earned $75 million, including at least $10m gained from license deals with Microsoft (Battersby, 2024a). Elsevier has partnered with three firms, primarily in the biomedical industry to provide “data and information from hundreds of medical journals and other verified sources” (Elsevier 2023). While Sage announced that they are presently “in talks” to begin licensing works (Battersby 2024c), they note that “we have reason to believe many tech companies have already harvested much of our content to train large language models … we believe that a preferable route is to offer clear licensing routes to our content that protects rights and include payment for the use of content by the LLM that we can pass on to authors and societies”. However, this decision was made without clear consent from participating journals, and writers themselves are unlikely to receive a cent of these profits. Rather, publishers like Sage have recognized that the rights of their authors have been abused for the profit of tech firms, and, instead of instigating legal action to protect these rights, have chosen to accept their slice of these profits.

As in all forms of accumulation by dispossession, this present expropriation of ownership from labor has been built off prior acts of dispossession, as the ability for these publishers to profit from the theft of our works was dependent on their monopolistic accumulation of intellectual capital into a select few outlets. Publishers own vast quantities of our writings as forms of sellable data assets, which accrue an exponentially large value through the centralized hoarding of texts which would hold little value individually. Through the consolidation of the academic industry into a set of only four major parties, nearly all participation of this system is dependent on providing value to these institutions, while our labor remains unpaid. The consolidation of these firms would position them with a strong opportunity to actively seek to legally challenge the AI industry’s theft, as they have access to financial resources and institutional support far beyond what any individual author may have. However, rather than seeking to protect the rights of their unpaid laborers from plagiarism or competition from the many tech firms hungry to replace higher education with chatbots, they have allied with these data firms to legitimize their expropriated content.

Open Access journals and papers will by default have been scraped, though certainly the public availability of this information outweighs the lack of protection against its appropriation by data firms, as even restricted-access works have been pirated for these models. Rather than advocate for further restricting access to information, it is rather the complicity and active participation of our hosting publishers which we must oppose, for their profiting off of this expropriation of our rights with no direct compensation or consent from authors.

While I’ll not unilaterally declare a boycott against publishing services in this short essay, it is necessary for authors, the Antipode Foundation, and all research organizations to critically discuss how to respond to these practices, the degree to which they should be addressed, and what legal/economic/activist methods can be organized in opposition to this enclosure and appropriation of our labor from both publishers and AI companies. The current US administration is incredibly favorable towards domestic AI firms, infusing the industry with 500 billion additional dollars of public cash and banning the use of foreign equivalent services. As with all past eras of accumulation by dispossession, the state has played a key function in legitimizing the gains which capital has acquired through extra-legal means. As such, legal action within the US appears unlikely to succeed, through attempts in the EU may fare better (Fontana 2025). Towards a short-term goal, we must push publishers to produce an option to meaningfully opt out of their licensing agreements with AI companies and big data firms. Academia would also do well to ally with creatives in art and entertainment currently voicing similar concerns.

As in all eras through which new technology is used to separate workers from the products of their labor (see Hobsbawm 1952), it is necessary to fight for consolations and protections for workers. In such moments when industrialists carry the full support of the state and capital to build tools which alienate workers from their labor, it has been necessary to actively fight for concession and protection. The vast libraries of historical action available to critical geographers (the very libraries which data firms have sought to appropriate) provide opportunities and insights for action today.

References

Battersby M (2024a) Taylor & Francis set to make £58m from AI in 2024 as it reveals second partnership. The Bookseller 25 July https://www.thebookseller.com/news/taylor-francis-set-to-make-58m-from-ai-in-2024-as-it-reveals-second-partnership (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Battersby M (2024b) Wiley set to earn $44m from AI rights deals, confirms “no opt-out” for authors. The Bookseller 30 August https://www.thebookseller.com/news/wiley-set-to-earn-44m-from-ai-rights-deals-confirms-no-opt-out-for-authors (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Battersby M (2024c) Sage confirms it is in talks to license content to AI firms. The Bookseller 19 September https://www.thebookseller.com/news/sage-confirms-it-is-in-talks-to-license-content-to-ai-firms (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Birch K and Ward C (2024) Assetization and the “new asset geographies”. Dialogues in Human Geography 14(1):9–29 https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221130807

Carlini N, Ippolito D, Jagielski M, Lee K, Tramer F and Zhang C (2022) Quantifying memorization across neural language models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2202.07646

Carpenter T A and Jarrett J (2024) Wiley leans into AI. The community should lean with them. The Scholarly Kitchen 31 October https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2024/10/31/wileys-josh-jarret-interview-about-impact-of-ai/ (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Doorn N and Badger A (2020) Platform capitalism’s hidden abode: Producing data assets in the gig economy. Antipode 52(5):1475–1495 https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12641

Elsevier (2023) Exclusive: New partnership aims to help doctors harness AI to diagnose patients. 15 November https://www.elsevier.com/connect/exclusive-new-partnership-aims-to-help-doctors-harness-ai-to-diagnose (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Elsevier (2025) Scopus AI: trusted content. Powered by responsible AI. https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus/scopus-ai (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Fontana A G (2025) Web scraping: Jurisprudence and legal doctrines. Journal of World Intellectual Property 28(1):197–212 https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12331

Harvey D (2003) The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hicks M T, Humphries J and Slater J (2024) ChatGPT is bullshit. Ethics and Information Technology 26(2) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-024-09775-5

Hobsbawm E J (1952) The machine breakers. Past & Present 1(1):57–70 https://doi.org/10.1093/past/1.1.57

Kaun A and Stiernstedt F (2020) Prison media work: From manual labor to the work of being tracked. Media, Culture & Society 42(7/8):1277–1292 https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719899809

Marx K (1976) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume One (trans B Fowkes). London: Penguin

Mezzadra S and Neilson B (2017) On the multiple frontiers of extraction: Excavating contemporary capitalism. Cultural Studies 31(2/3):185–204 https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2017.1303425

Milmo D (2024) Thom Yorke and Julianne Moore join thousands of creatives in AI warning. The Guardian 22 October https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/oct/22/thom-yorke-and-julianne-moore-join-thousands-of-creatives-in-ai-warning (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Morales J (2025) Meta staff torrented nearly 82TB of pirated books for AI training—court records reveal copyright violations. Tom’s Hardware 9 February https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/artificial-intelligence/meta-staff-torrented-nearly-82tb-of-pirated-books-for-ai-training-court-records-reveal-copyright-violations (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Posada J (2022) “The Coloniality of Data Work: Power and Inequality in Outsourced Data Production for Machine Learning.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Toronto https://utoronto.scholaris.ca/items/6c242cbc-4a24-48fc-9859-6ab25c22025f (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Reisner A (2023) Revealed: The authors whose pirated books are powering generative AI. The Atlantic 19 August https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/08/books3-ai-meta-llama-pirated-books/675063/ (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Saul S (2025) Yale suspends scholar after AI-powered news site accuses her of terrorist link. The New York Times 12 March https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/12/us/yale-suspends-scholar-terrorism.html (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Seife C (2023) Don’t blame AI. Plagiarism is turning digital news into hot garbage. Scientific American 28 September https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/dont-blame-ai-plagiarism-is-turning-digital-news-into-hot-garbage/ (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Thatcher J, O’Sullivan D and Mahmoudi D (2016) Data colonialism through accumulation by dispossession: New metaphors for daily data. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 34(6):990–1006 https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816633195

Wiley (2024) Advancing the pace of research through AI. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/media/ai-partnerships (last accessed 7 April 2025)

Yan J (2024) Techno-feudalism as primitive accumulation: A Marxist perspective on digital capitalism. Critical Sociology https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205241302838