Sara Salem, London School of Economics and Political Science

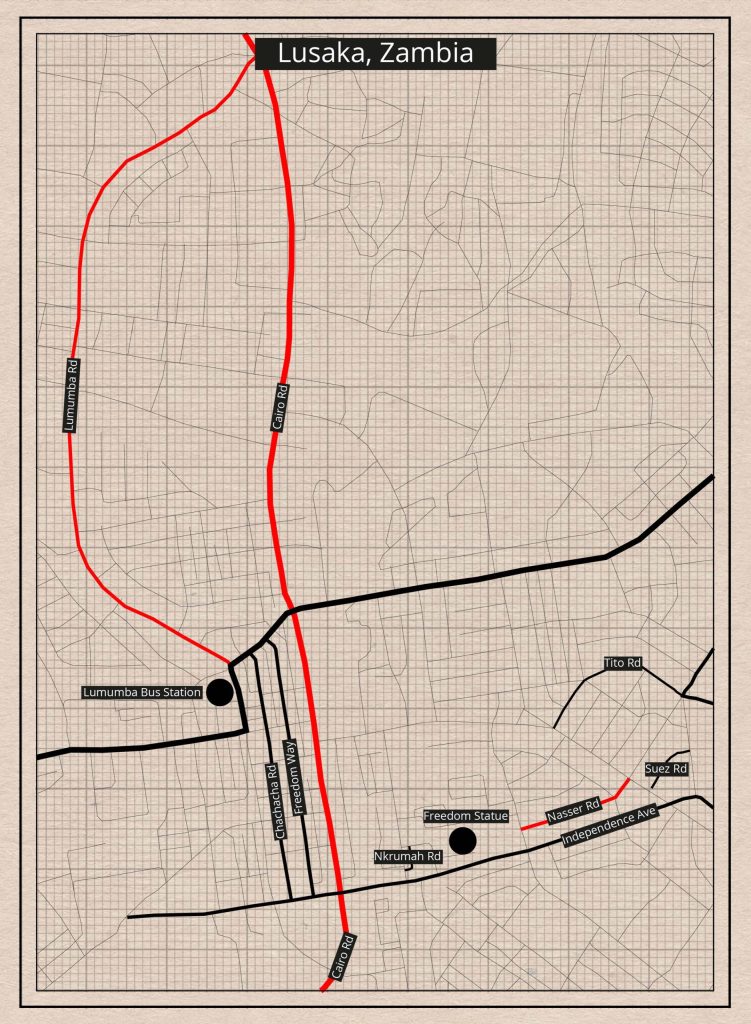

Growing up in Lusaka, Zambia, I distinctly remember Cairo Road, one of Lusaka’s main thoroughfares named after the city my father was from. I remember it always being busy, noisy and full of traffic; an artery through the city that connected different neighbourhoods. It was a street I usually found myself on during the weekends, when my parents had some errand or another at one of the shops or offices located there. I can immediately conjure up its soundscape, see the buildings lining each side, and recall the faded street sign telling us we’re on Cairo Road.

At the time, I thought the name of the road represented a concrete connection between Egypt and Zambia that had possibly been created during the 1950s or 1960s when both countries were experiencing anticolonial revolutions. Cairo Road was surrounded by Tito Road, Lumumba Road, Independence Avenue, Nkrumah Road, Freedom Way, and many others, mapping out a cartography of shared struggles for independence. To me, it represented the connections between Egypt and the rest of the African continent that I knew existed because I had grown up hearing about them. This road was proof that, not so long ago, anticolonialism had connected two countries that today rarely appear in the same constellation of understanding.

Many of Lusaka’s roads named after anticolonial figures or moments acquired their names following decolonisation, having initially been named after colonial figures; for instance, King George Avenue later became Independence Avenue and Cecil Rhodes Drive was renamed to Addis Ababa Drive. In the newly postcolonial city, renaming became a way to reorder space; a way of “claiming the city back” and symbolically rebuilding it. As such, place names were a key site of anticolonial struggle (Çelik 1999: 69). Indeed Zambia itself had previously been known as North Rhodesia. This process aimed to produce a different set of political attachments, and while these changes may appear discursive, it is their embedding in concrete spaces, though signs, maps, placards, statues and so on, that make the names come to life in the everyday. Street naming practices have been written about extensively, showcasing that it is one way in which the past comes into the present, “weaving history into the geographic fabric of everyday life” (Alderman 2002: 99). Naming practices bring to the surface contestations over how space is understood and who it is seen as belonging to,[1] and the very act of naming says something about an attempt to inscribe meaning into an everyday space, asking for something to be remembered (Rose-Redwood 2008: 435). In this vein the renaming of streets during decolonisation marked a practice of contesting the production of colonial space, and a shift to the construction of a postcolonial city; Third Worldism is made present in the spaces people encounter in their everyday lives, producing meaning around an evolving project of liberation.

Renaming the postcolonial city was about the past and present, but also the future; it ensured that these material markers would be experienced by people who were not involved in the political struggles that made these new names possible. As such, they intimate towards a promise of a future in which colonial and postcolonial are established as distinct temporal moments with firm boundaries, and in which anticolonial struggle is no longer the dominant frame of space-making. If these material markers can be experienced in the present as a battle over space that was won, they also signal what has been lost. A street in Lusaka named after an Egyptian or Algerian political figure made more sense 60 years ago than it does now; we rarely see Pan-Africanism recalled today as an anticolonial project connecting the entire continent, or encounter the possibility that Egypt and Zambia are part of the same political project cultivated around social justice and political liberation. Instead, Egypt and Zambia seem much more distant today than the presence of these street names suggest; while they were both arguably centres of anticolonial resistance in the mid-20th century, today they are modelled after different kinds of neoliberal projects. It is in this sense that markers such as these street names also represent what has been lost, marginalised, or forgotten.

Despite this, they continue to signal a past that cannot be erased, an inscription of anticolonial power into the materiality of the city.[2] Today these traces of an anticolonial past appear faded, having lost the vigour they once possessed. Yet they are often all we have left of past revolutionary moments. The properties of these traces mirror the faded history they represent; yet this does not make them inert. One can read these traces as waiting, their power never completely evacuated, even when the political moment that created them comes to pass. They hold revolutionary potential, I suggest, simply because they can become reactivated through encounters with them. My own encounters with Cairo Road, for instance, conjured up an anticolonial past and allowed me to imagine Zambian–Egyptian solidarity as something that existed at one point in time, and perhaps something that could exist again. In this sense, the Pan-Africanism of the 20th century remains a possibility rather than a faded project.

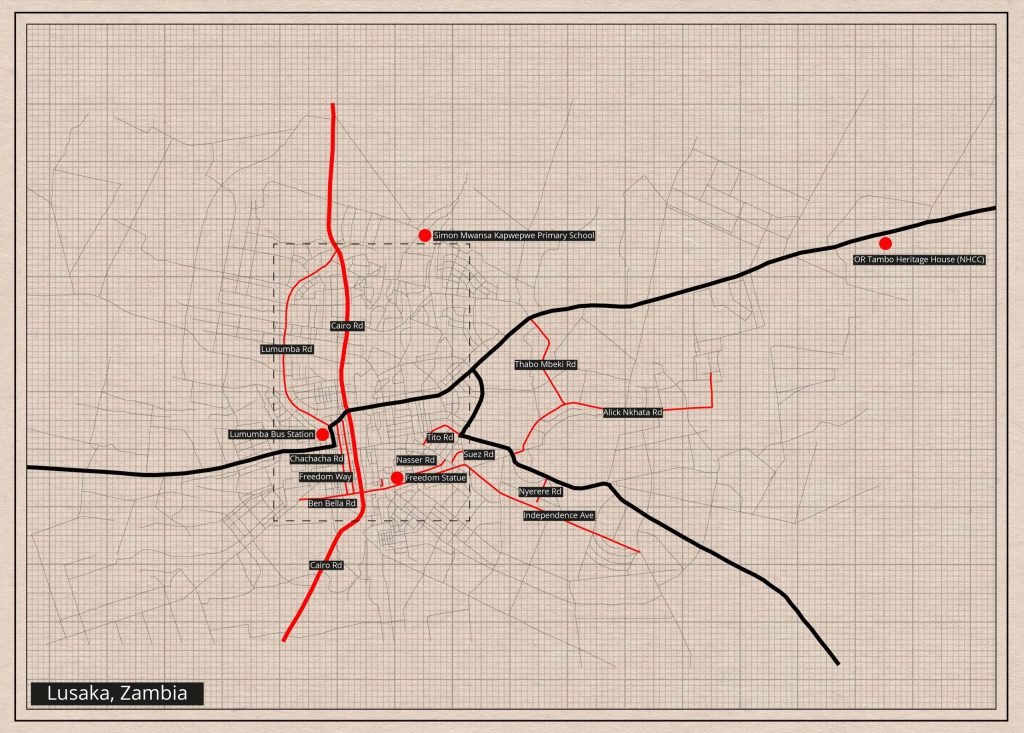

In a photograph book entitled Avenue Patrice Lumumba, Guy Tillim travelled across Southern and Central Africa in search of traces of Lumumba in the architectural landscape (Tillim and Gardner 2008). He might have encountered Lumumba Road and Lumumba Bus Station in Lusaka, though they do not feature in the volume. The photographs Tillim takes are of ordinary scenes: a child walks down a tree-lined road; laundry hangs from wired lines; concrete buildings dominate the shot. There is something about this juxtaposition of streets named after the faded promises of anticolonialism alongside ordinary scenes from the postcolonial city that seems to suggest that life goes on. Yet these traces are not simply relics of the past, despite their material appearance; they exist always with the possibility of being reactivated, disrupting time and dragging anticolonial promises into the here and now. They are alive and agential; they do something, even if this something depends on who is seeing, feeling and sensing them, and when the encounter happens. I am thinking here of my own affective responses to Cairo Road. When I was younger, I noted offhandedly that this street name was some kind of connection to Egypt, a place I also belonged to in some way. It was only later, as my research interest in anticolonial internationalism grew, that I saw the road as a possible trace of an important moment in history. I thus encountered this road differently at different moments of my life, projecting different meanings onto it each time yet nonetheless noticing it as a trace of something.

The photographs collected in Tillim’s archive represent what Leora Maltz-Leca (2011) calls a “cartography of liberation”:

Looking at Tillim’s photographs, it seems that for every dream of revolutionary struggle, there is an avenue Patrice Lumumba … As Tillim finds and refinds Lumumba’s ghost in the thoroughfares named for him, his photographic essay draws together these dispersed avenues into a spectral cartography of liberation, uniting a network of scattered locales through their identification with this iconic figure. Such an imaginary cartography—a route linked by a name—highlights how naming, as Paul Carter has eloquently argued, is bound up with the writing of the landscape into history.

Calling avenues named after Lumumba “avenues of dreams”, Tillim gestures towards the utopian future through capturing the faded traces of anticolonialism and decolonisation. Street names, broken statues and faded plaques become an invitation to the present to cite anticolonial pasts that seem far away from us, even as they continue to shape the world we live in.

I was later to discover that my memory of Cairo Road was imprecise. Cairo Road had actually been named after a project by the infamous colonialist Cecil Rhodes to connect Cape Town and Cairo. This reality couldn’t have been further from what I had been projecting onto the road. The correct object of my political imagining, or longing, would have been Nasser Road, named after Gamal Abdel Nasser, and not too far from Cairo Road. The imprecision of this childhood memory, though, does not render it completely useless; it brings to light the ways in which memory and politics are bound up with objects and stories all around us, producing both imprecise and highly seductive feelings. The projection of my nostalgic desires onto a road that ended up being a representation of colonial rather than anticolonial power zeroes in on the blurry temporal lines between these varying political projects.

The memory itself—though misdirected—still tells a story of entanglements between Egypt and Zambia. These connections were part of an anticolonial imaginary, a moment during which Egypt was part of the Pan-African project. There are Nasser Roads all over Africa, from Mombasa to Kampala, Mwanza to Luanda to Tunis. Many of these Nasser Roads signify a historical moment that is difficult to imagine today, during which Pan-Africanist futures spanned the entire continent, disrupting the various structures and histories that reproduce North Africa as separate from the rest of the continent, or Egypt as Arab first and foremost. Growing up, I always thought of and understood Egypt as part of Africa, and as connected to rather than different from countries like Zambia. The term “Middle East and North Africa” was not part of my register, neither was the idea of “sub-Saharan” and “North” Africa as two separate zones. Egypt and Zambia were part of the same space, without being identical or even similar to one another. And yet, this is not necessarily the way most Egyptians imagine Egypt today, where a certain Arab identity can often be constructed as more “natural”. This is also not how many people in Zambia imagine Egypt today; often, people would comment that Egypt had been closer to the rest of Africa under Nasser, but that this had changed since then. These understandings—not representative but anecdotal—are interesting in what they reveal about Egypt’s shifting positioning in relation to Africa.

Historical events such as the Trans-Saharan slave trade begin to tell a story of how the North has historically been constituted as racially superior and somewhat separate from Africa, closer to the Arab world. Egypt’s Arab identity has guided the formation of many of its archives from the colonial and anticolonial period, and is hegemonic in readings of Egyptian politics today. It is in this context that the anticolonial moment of Pan-Africanism becomes disruptive, signifying a historical moment that is difficult to imagine today because of the marginalisation of Egyptian Pan-Africanism. To revisit this moment is to recognise events that otherwise slip out of view. In a contemporary time marked by increasing attention to racism in North Africa and the historical realities of enslavement and Arab racism, these disruptive traces from the recent past posit a different mode of political solidarity, one in which a Pan-African project stretching across Africa can be remembered.

From the vantage point of the present, however, the future imagined through the renaming of space and the supposed victory of anticolonial struggle remains shaky. Today Egypt’s political project, led by Abdelfattah El Sisi, is oriented towards Egyptian dominance and extraction in relation to Africa, replicating older patterns while itself bound up in political economic dependency with the Gulf states (Hanieh 2013). Yet this is why this disruption—recalling a moment during which Pan-Africanism was a political project stretching across the entire continent—matters; it counters any notion that there is a natural political, economic or racial order across the continent and points to the possibility of solidarity as a means of reorienting colonial geographies. This disruption is a reminder that things can be—and have been—otherwise. Zooming out of the map of Lusaka, away from Nasser Road, Cairo Road soon comes back into view. These two roads—both referencing Egypt—signify these radically different histories, power relations and futurities; one representing colonialism, the other anticolonialism.

In other words, the presence of streets named after anticolonial figures such as Nasser across postcolonial cities does not necessarily signal the power of an anticolonial narrative to structure the landscapes of these spaces, nor that there is a conscious attempt by governments to bring the anticolonial past into the present—a present that is, after all, not only very different from the anticolonial past but can even be understood as a betrayal of it. They signal instead to the impossibility of erasing these traces from the landscape and from public memory; they remain fixed in place, part of everyday life, reminding those in the present that there was a possibility of an alternative present. This is the power of these material traces; they bear witness to the future that was imagined when they were put in place, when the renaming took place. It is in this sense that they are disruptive, referencing a past that can never quite be forgotten. They bring the anticolonial past into the present, unearthing solidarities that have been inactive for decades. They disrupt ideas around who is African, and how past struggles may have answered this question differently.

Visiting Lusaka this month (September 2025), after many years away, took me back to my memories and experiences growing up in this city that oriented me to a global cartography of anticolonial struggle. It doesn’t seem to me, anymore, that what I ended up later working on—anticolonial histories and anticolonial archives[3]—was a coincidence, or an accident of research. Lusaka was a central node of anticolonial solidarity, one of the first countries to become independent in Africa. Zambia hosted liberation movements from all over Southern Africa, from SWAPO to the ANC, understanding that liberation was not meaningful if it meant liberation for only some. Lusaka’s map is a living archive of this solidarity, a cartography of anticolonial resistance and struggle, a collection of faded dreams that lie in the background, waiting, but always potentially revolutionary.

Endnotes

[1] In an article on New York City’s streetscape, Reuben S. Rose-Redwood (2008: 433) argues that street naming is a form of marking geographic space that works through places of memory and of erasure.

[2] Growing up, I was always struck by how similar Egypt and Lusaka were in terms of space. How to explain similar buildings, squares, roads, and statues? British colonialism was one answer, and indeed both countries had been British colonies for decades. Another answer was decolonisation, which produced street names that were similar in both cities, as well as familiar motifs of flags, national heroes, and prominent figures such as the first leaders of independent Zambia and Egypt, Kenneth Kaunda and Gamal Abdel Nasser.

[3] See the 2025 Antipode RGS-IBG Lecture, “Sonic Lives: On the Radio and Anticolonial Solidarity”, presented by Mai Taha and Sara Salem on 27th August: https://antipodeonline.org/2025/08/26/the-2025-antipode-rgs-ibg-lecture/ (last accessed 6 November 2025).

References

Alderman D H (2002) Street names as memorial arenas: The reputational politics of commemorating Martin Luther King Jr. in a Georgia county. Historical Geography 30:99-120

Çelik Z (1999) Colonial/postcolonial intersections: Lieux de mémoire in Algiers. Third Text 49:63-720

Hanieh A (2013) Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East. Chicago: Haymarket

Maltz-Leca L (2011) On street names and “de facto monuments”: Guy Tillim’s Avenue Patrice Lumumba. ArteEast 1 September https://web.archive.org/web/20120125110238/http://www.arteeast.org/pages/artenews/takemeonthiswalkagain/714 (last accessed 3 October 2025)

Rose-Redwood R S (2008) From number to name: Symbolic capital, places of memory and the politics of street renaming in New York City. Social & Cultural Geography 9(4):431-452

Tillim G and Gardner R (2008) Avenue Patrice Lumumba. Munich: Prestel